Overcoming Extreme Poverty in Europe | Joseph Wresinki

In 1957, six European countries founded the “European Economic Community”. Thirty years later, in a June 1987 editorial, Joseph Wresinski expressed his disappointment that extreme poverty continued to exist across EEC member countries. He describes his political vision for Europe and says that the idealism of young people gives him hope for its future.

His words could easily have been spoken today. Although the EEC became the European Union in 1993, extreme poverty still exists in all of the member countries. There is an urgent need for policies that reduce social and economic exclusion. There are signs of progress, however. The recently enacted French law that prohibits discrimination against people in poverty is a hopeful step forward.

In the editorial below, Wresinski expresses his radically hopeful belief in the power of idealism, especially among young people. These words could also have been spoken today:

“Young people continue to join us, not because of what their elders can teach them, but because of what they can prove with their lives… their passion, and their loyalty to families in poverty.”

As ATD Fourth World celebrates its 60th anniversary in 2017, it still provides a way for people of all ages, nationalities, and faiths to speak out about poverty and to live out their ideals of working towards social justice. We are thrilled that, over those 60 years, so many people have chosen be a part of ATD and to act on the ideals that Joseph Wresinski speaks of below.

We need you to realize the hopes and dreams of people living in poverty — in the European Union and around the world – to build a more just and peaceful world where everyone has the same opportunities.

Find out how you can help ATD by:

- working with a grassroots project

- becoming a member of our Volunteer Corps, or

- supporting our work with donations or in many other ways

- participating in the 2017 campaign

The Europe that Will Arise from Overcoming Poverty

By Joseph Wresinski

In all European Community member states, there are adults who have no job qualifications and who live in long-term — even permanent — unemployment. Most of them are parents, heads of households. Their children are the furthest behind at school and some leave without knowing how to read and write; and their teenagers do not find jobs.

We hoped that coming together in a European entity would lead extreme poverty to disappear; but instead poverty continues to be perpetuated throughout the Community. Children, young people, adults, and families in poverty look at the world changing. They look at us from the depths of their shoddy, overcrowded apartment blocks and neighbourhoods. Dependent on our social welfare systems, which only help them scrape by, they observe the great political transformations from afar, in silence. They do not participate in the changes because they do not belong to unions or have access to a community life that could promote their interests. They are free citizens only in theory, only in so far as constitutions are concerned. In reality, they derive no benefit from these constitutions.

We came to realize that it has not been the recent economic crisis or changes in the economy that caused a re-emergence of acute poverty. In fact, the European Community simply inherited persistent poverty thirty years ago and has continued to bring it into the future.

This poverty, however, surely escalates and becomes more visible as States reduce their expenses and revise their priorities. The people who live in the deepest poverty, those with the least schooling and the worst housing, are not included in the priorities of any Member States.

Moreover, the lowest-income households suffer the harshest consequences when we cut back our social insurance systems. Worse, in most States, these cutbacks have excluded long-term job-seekers from benefits that protect the dignity of workers. Throughout the European Community, they have been relegated to this Europe of dependence, where they struggle, and from which it is not easy to return to a Europe of participation. Thus a spotlight is turned towards deep poverty and the isolation of the very poor, who are fenced into a Europe of uselessness and shame. And yet, extreme poverty existed from the very beginning; and from the beginning of the European Community, people in the deepest poverty have raised this key human rights question.

The essential question is not whether we were right to start out with an economic union, or whether in the future Europe will have a military or political union. The essential question is what families in extreme poverty have been asking since 1957: no matter if the union is economic, social, or cultural, are we also working towards a Europe for all Europeans? In whatever domains Europe unifies, will all Europeans have equal opportunities to exercise their rights and responsibilities?

Today we know that the economic union has not succeeded in providing rights for everyone. There was nothing wrong with starting our union in the economic sphere; but while our economies were being linked, they all still incorporated persistent poverty as part of their structures. When we were bringing our economies together, nothing was done to examine extreme poverty or to eradicate it. An economic union that excluded people living in poverty could only lead to a Europe that would also exclude them and ignore human rights.

We could say that Europe forgot, didn’t know enough, or presumed too much. We could say that Europe didn’t think deeply enough. It assumed that, through its economic achievements, it could defeat the most serious scourge of all times: persistent poverty. There was probably more lack of reflexion than lack of good will, because thousands of years of civilisation have led us to always ask questions about justice and peace; they have led our nations to be forward-looking, always concerned about change, progress, and renewal. Justice, peace, and inalienable rights are part of this constant search for innovation, even when they conflict with the material progress and technical efficiency that the human race thinks it needs in order to have more control over an unknown future. We inherited values that have withstood our political and technological revolutions. The young people of our own time inherited them too.

It is clear that young people do not accept the inevitability of old wrongs. They refuse injustice, oppression, and poverty intuitively for the sake of values whose origins they barely understand. Young people know little about the context and the interdependent nature of human rights. They know little about the thousands of years of thought, of effort and of struggle against this unbearable injustice against men and women who have been scarred by their situation of poverty and considered less than human beings. But throughout the ages, Europeans refused to accept this insult to humankind, and young people also inherited the determination to overcome poverty.

Young people will have to continue building this Europe we are talking about, this Europe we are bringing into existence. We should tell them about the history that led us here, the heritage left to us, and we should explain what we did with it. And we must consider that they need to get practical experience so that they can conduct European affairs in the future.

We have to be honest with them. It is their right to know the truth; but above all, it is the right of people living in extreme poverty. They deserve to be able to count on young people who will not abandon them in this Europe of dependence where we have exiled them, young people who will take up our baton of good will, of our hoping against hope, and of our unfinished and inadequate progress on human rights. And they should be able to count on young people who will also correct our mistakes and progress further than we have because we will have told them what we know.

The ATD Fourth World Volunteer Corps is one of the places where information flows, where experience is gained every day, where we work toward a Europe that would give the highest priority to people who live in the deepest poverty. ATD was founded in 1957, the same year as the European Economic Community was formed. From day one, all of our volunteers have taken a pan-European approach, never thinking that dire poverty was an issue of merely domestic concern, for each country to tackle alone. Faced with the wrongs done to compatriots who lived in poverty, French, Germans, Dutch, Belgians, Britons, and others joined forces. They saw that extreme poverty repudiated the human race, negated its rights and responsibilities, and thus rejected thousands of years of European history. If Europe were to accept this injustice, it would never be credible.

The Volunteer Corps continues. People who were young when ATD was founded now lead their adult lives as defenders of human rights. Young people continue to join us, not because of what their elders can teach them, but because of what they can prove with their lives, their struggle, their passion, and their loyalty to families in poverty.

If we want to build a united Europe, we should wholeheartedly support this Volunteer Corps that was born out of European history. It is our guarantee that the outcome we have been striving towards is worth the effort, and that to progress further in the future our doors remain wide open.

The editorial was first published in French in the Revue Quart Monde, issue n°124/1987.

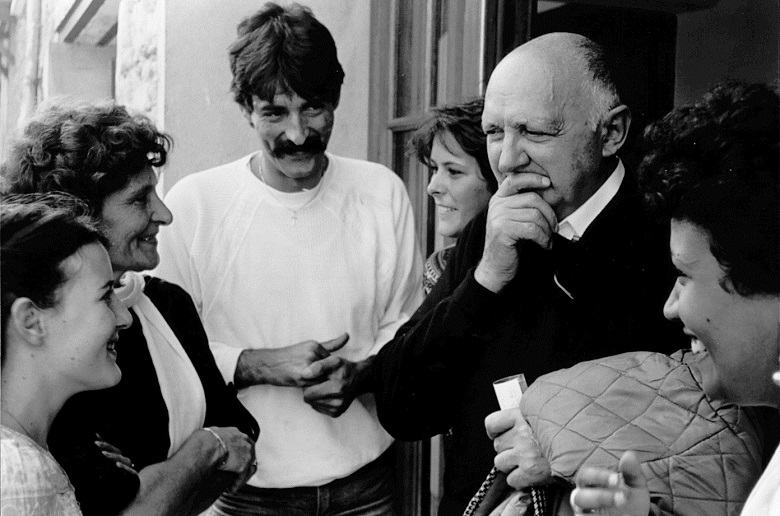

Photo ATD Fourth World: Joseph Wresinski, with young people at the10th anniversary of the Champeaux Youth Centre (6 October 1985).