I’m Just a Student. How Can I Help Overcome Poverty?

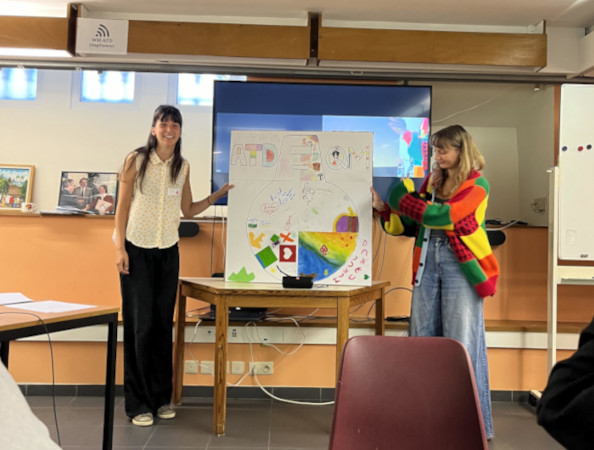

Above: ATD Fourth World event in Brussels

By Ana Patricia Romay Febres

![]() Reading time 6 minutes

Reading time 6 minutes

Poverty is a deeply multidimensional experience. According to ATD Fourth World, poverty involves disempowerment and a daily struggle for dignity. Of course, it includes the denial of decent work, insufficient and insecure income, and material and social deprivation. But it also stems from how people in poverty are perceived and treated—through social and institutional maltreatment and the lack of recognition for their contributions. These dimensions are closely interrelated and shaped by broader factors like identity, culture, and environment: it is structural, multilayered, and it should be approached as such. As students, we often find ourselves asking: What power do we have in the face of such a massive issue? How can we contribute meaningfully to a global challenge that seems far beyond our grasp? We can start by acknowledging the immense privilege it is to study—a privilege that many people are denied. Education is not just a means to a personal end, a job, an income, an isolated purpose. It is a tool we can use in solidarity with others. But how do we begin to put this into practice?

The power of attention, solidarity, and commitment to justice

These are the questions I have been grappling with throughout my internship with ATD Fourth World, an international anti-poverty organization that works in partnership with people who have experienced poverty firsthand. Through this work,

I’ve come to believe that while students may not have access to traditional levers of power—money, political office, institutional leadership—we do hold a form of power that is quieter, but no less important: the power of attention, solidarity, and commitment to justice. Our actions may be small, but they are not insignificant.

Radical shift

ATD Fourth World is grounded in the belief that people living in poverty must be at the heart of efforts to end it. This approach radically shifts how we think about social justice: from helping people with lived experiences of poverty to working with them, learning from them.

Through my internship with ATD, I’ve learned that poverty is not only material. It is emotional, social, and spiritual. It is about exclusion, silence, and shame. But it is also about resilience, resistance, and dignity.

Through ATD’s participatory approach, I’ve seen how change starts by listening. One of their core methodologies, the Merging of Knowledge, was developed in 1993 to create spaces where people living in poverty could reflect and contribute as equals alongside academics and practitioners. This inclusive approach challenges traditional hierarchies in research by recognizing that people living in poverty carry valuable, generational knowledge. A prerequisite in the work to overcome poverty and social exclusion is the recognition of people in poverty as actors in their own right—not passive recipients of aid or research subjects, but central participants in shaping solutions.

A heavy sense of despair

In sharing my work with ATD with my friends—particularly with Maria, a 21-year-old Mexican student in the US studying Philosophy, Dance, and Political Science—I’ve realized that many students today carry a heavy sense of despair. We talked about the pressures we face: the burden of student debt, the need to work multiple jobs, the fear of disappointing our families, and the ever-rising cost of just existing. All of this unfolds against the backdrop of increasing hate, polarization, and institutional neglect.

Maria and I spoke about how lonely it can feel to care deeply in a world that often seems indifferent. Yet in our conversation, we also found strength in each other. We reminded ourselves that love is political, that care is radical, and that friendship—true, empathetic, engaged friendship—can be a form of resistance. When we show up for one another, when we volunteer, when we notice those around us who are struggling, we are already challenging the systems that isolate and dehumanize us.

A powerful drop

Volunteering for an organization like ATD might feel like a drop in the ocean—but it is a powerful drop. It challenges the idea that we are powerless. It reaffirms that collective action starts with small, everyday decisions. It gives us the chance to connect our academic knowledge with real-world struggles, and to remember that theory without action is empty.

As students of international relations, political science, or philosophy, we are often told that the real career opportunities—and the real money—are in security, foreign policy, or consulting. Work in development or anti-poverty advocacy is too often dismissed as idealistic, “soft,” or financially unviable. But this mindset is part of the problem.

If we want a world where human dignity comes before profit, then our choices—where we intern, what causes we support, what careers we pursue—must reflect that.

Being in our twenties right now can feel like standing at the edge of a cliff. We have more access to information than ever before, but this access also overwhelms us. We know about every injustice in the world and yet feel unable to stop them. We are constantly told we are the “future,” but we are living in a present that is on fire—literally and metaphorically.

Capable of transformation

Still, I believe that we are a generation capable of transformation. If there is a unifying feeling among us, it is a shared sense of helplessness. But paradoxically, this shared helplessness can be a source of power. It connects us across borders, disciplines, and identities. It urges us to abandon individualism and embrace the collective.

Because alone, change is impossible—but together, it is inevitable.

Whether it’s attending a community meeting, reading a book by someone with lived experience of poverty, or just starting a conversation, every step matters.

For Maria and me, these small acts are already reshaping how we see ourselves—not as helpless bystanders, but as agents of change. And that’s something we can all become, no matter how busy, helpless, or burdened we feel.

Poverty is not a problem that will be solved overnight. It is historical, systemic, and deeply entrenched. But it is not immovable. As students, we have the chance to redefine what power looks like. We can choose empathy over apathy and justice over cynicism. Our studies are not separate from the real world—they are part of it. And the more we integrate what we learn with how we live, the more meaningful our education becomes.

The work to overcome poverty begins with us—not because we have all the answers, but because we are willing to ask the right questions and walk alongside those who’ve been ignored for too long. In that journey, we may find not only purpose, but each other.