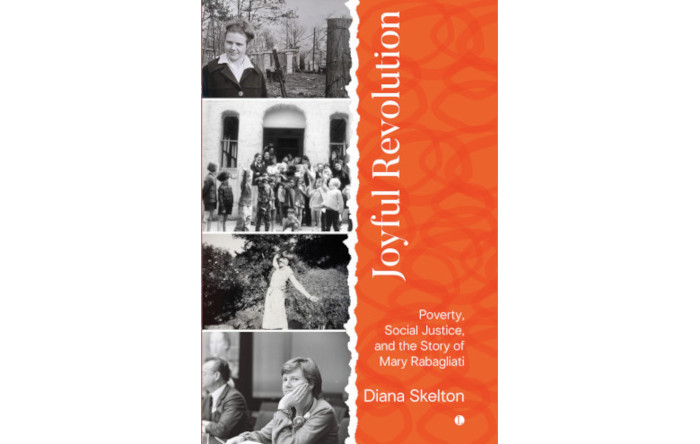

Poverty, Social Justice, and the Story of Mary Rabagliati

![]() Reading time 8 minutes

Reading time 8 minutes

Diana Skelton, originally from the Washington D.C. area, is an ATD Fourth World Volunteer Corps member. She is the author of Joyful Revolution: Poverty, Social Justice, and the Story of Mary Rabagliati (if you are in France or Belgium, you can buy it here), published by the Lutterworth Press. Below, Diana talks about Joyful Revolution, why she wrote it, and Mary Rabagliati’s lifelong dedication to social justice and anti-poverty work.

What is Joyful Revolution about? Who was Mary Rabagliati? Why did you write a book about her?

In 1962, Mary Rabagliati joined Joseph Wresinski in co-founding ATD Fourth World. Here is how she described her first arrival at the emergency housing camp in Noisy-le-Grand where Wresinski was just beginning to develop the anti-poverty movement that would become ATD:

- On a dark misty February evening, I got off the bus and walked down the tarmac road. Suddenly the tarmac became only a dusty potholed path. The nearest bus stop was hundreds of metres away from the camp. The road stopped, and you had to walk in the dust – or the mud – to a place where everything was filthy. There were rats all over. People were living there! I was really shocked.

At the time, Wresinski was 45 years old, while Mary was only 20. He was French; she was British. He was a Catholic priest; she was an Anglican who convinced him that some of his church’s positions were unfair to women in poverty. They collaborated well; but had vastly different approaches. The book is about her origins before meeting him and also her role in shaping the way ATD developed over the years.

Who is this book for?

Before joining Wresinski, Mary worked as a secretary. She said:

- I wanted something else – but what? I knew what it is to earn money, go home, and do your own thing. It didn’t suit me. I thought it was a waste of time helping to get somebody else rich and then going out spending your salary. I was looking for something meaningful to do.

Once she discovered the camp in Noisy-le-Grand, she said:

- The conditions were indescribably terrible. These people made me realise that my life was shallow, empty, and futile.

I think this book is for anyone who feels the same: that life becomes more meaningful when you have the chance to work with others to work towards social justice. Mary’s initial choice at age 20 led her to grapple with many challenges over the years as she searched for the best ways forward. There are no magic answers, but I think this book is useful for anyone searching for meaningful ways to make social change over the long term.

Mary was also particularly concerned about hardships faced by women and teenage girls in poverty facing violence, early motherhood and constant challenges to their right to raise their own children. Her life’s work connects to today’s ongoing conversations about poverty, human rights, and gender equality, making it a compelling read for many social justice activists.

How can Mary Rabagliati’s lifelong dedication to social justice and anti-poverty work encourage young people nowadays?

When Mary began with ATD Fourth World, she was much younger than her teammates. Over the following decades, she always connected strongly with young people, seeking them out and making time to listen to their concerns. While she never minced her words and had her own strong views against anything dogmatic, her frankness and authenticity helped her to build bridges with people of very different backgrounds.

Throughout her life, she faced a wide variety of challenges in her work, and I find it inspiring to discover the approaches she tried: bursting with energy and ambition, but also firmly grounded in common sense and kindness.

Can you tell us a little about yourself and what brought you to write Joyful Revolution?

When I was 20, I met Mary Rabagliati as part of my training to join the International Volunteer Corps of ATD Fourth World. I was her housemate and then her teammate on several projects. Mary died of cancer six years after we first met. Our conversations made a lasting impact on my own life choices. Later on, I missed her, and often wondered what she would have gone on to accomplish if she hadn’t died so young. What I didn’t realise was that much of what she actually did accomplish was hidden from view. I was astounded in 2016 when I visited ATD’s archives and began reading Mary’s correspondence, interviews, and reports. I already knew that she spent a great deal of time and energy editing or translating other people’s writing; but I had no idea that she also made time to do so much writing of her own. The project that led me to Mary’s archives was nominally connected to preparing ATD’s 60th anniversary. But once I began sifting through Mary’s notebooks and reports, it struck me that I was exactly Mary’s age when she died. Outliving her made me feel a responsibility to tell her story to those who never met her.

There is a series of videos that you worked on about Mary Rabagliati’s life. Why was it important to also write a book?

For the video scripts, I really loved having Paul Maréchal’s artistic talents. He invented the format, combining a classic “draw-my-life” scenario with his own original watercolour backdrops. The dynamism of that matched Mary’s huge energy level. I’m also grateful to Naomi Anderson for voicing Mary in the videos, bringing Mary’s insights to life with her own modern-day sensibility. And several of you offered so much technical support to make the videos work—thanks a million!

But, as much as I love the videos, by the time we posted the final video to YouTube two years later, the project felt incomplete. Memories of Mary kept tugging at me. By then I was just beginning to discover that she had written much more than my initial research turned up. There was so much more that it felt important to tell.

Did you uncover anything surprising or fascinating in writing Joyful Revolution?

Mary got into trouble with the law or the military on three different continents! She also convinced a Catholic priest that women in poverty deserved access to the birth control pill.

But I think I was most intrigued by her approach to more daily challenges. She was always very frank: about times when she kicked herself for losing her temper; and also about frustration, exhaustion, and what she called “all of our day-to-day bitchiness”. She was working hard to build a movement for social justice; but she knew that the work isn’t only in big meetings at the United Nations or with members of Parliament. It’s also very much in the day-to-day hardships of poverty and all the reasons that people may behave harshly.

How did you choose the title ‘Joyful Revolution’, and what significance does it hold for you?

Mary’s life work was very revolutionary because it was a completely new approach to social justice. But she was also someone who made a point of seeking out joy everywhere, dancing as often as possible. She once said, ‘In the misery of poverty, joy matters even more […] so that people excluded from society can finally join in everything that makes the world extraordinary.’

Are there any specific influences that shaped Joyful Revolution other than Mary Rabagliati?

Part of the book is about how Mary’s work co-founding this anti-poverty movement resonate with my own experiences as part of ATD Fourth World. Like Mary, I have lived in the United States, France and the UK. Like her, I have travelled in South Africa, Kenya, Israel and Palestine. Like Mary, I work on the impact of poverty on the right to family life and social work. And also like her, I have grappled with the challenges of leading a diverse group of people who share a common goal but often hold widely divergent thoughts about how to achieve it. So while the book is mainly a biography focused on her lifetime, there are also several threads connecting us to the challenges we face in moving social justice work forward here and now.

One of her responsibilities with ATD Fourth World was publishing books and newsletters that would educate the general public about extreme poverty. Why was that so important to her?

Mary saw how society excluded people in poverty. In 1960s France, young people living in the emergency housing camp were not welcome in local dance halls. A young person in the UK in the 1980s told her:

- People think we young people are all ruffians. Police ask you to move on. Where I live, the road has a bad reputation. When people ask where I live and I tell them, they don’t want to know me. Everybody thinks you’re around to make trouble, so we’re always told to go away.

Mary knew how much people in poverty contributed to society, and she saw publications as a vital way to cultivate understanding about their aspirations and their unrecognised skills. Because the social dimensions of poverty isolate people, Mary knew that educating the general public is a vital step towards overcoming poverty.

And how can we keep her heritage alive?

I really hope that this book starts new conversations! Mary had so very much to say, and her challenging and dynamic voice can help inspire us for all the social justice work ahead of us today.