From Birmingham to Nairobi: Rights for Women and Girls in Extreme Poverty

This is the sixth in a series of videos retracing the life of Mary Rabagliati, one of the first volunteers to join Joseph Wresinski in founding what would become ATD Fourth World.

Play with YouTube

By clicking on the video you accept that YouTube drop its cookies on your browser.

It was very soon after Mary first joined Wresinski in 1962 that she travelled to Birmingham (United Kingdom). Her work there was supporting a woman pregnant with her eighth child and living in so much chaos that she could not hope to follow natural methods of birth control. This turned Mary into a staunch advocate for family planning at a time when the birth control pill had just been legalised in the UK for married women but not yet for single women.

A commitment to feminism was part of Mary’s family heritage. Her mother was a strong woman who spent eight years as a lone parent after her husband’s death. Mary’s father was the great grandson of a prominent suffragist in Scotland. That 19th century ancestor, Priscilla Bright McLaren, was the president of the Edinburgh Women’s Suffrage Society, which campaigned for women’s right to vote and to own property. McLaren also worked against slavery and poverty.

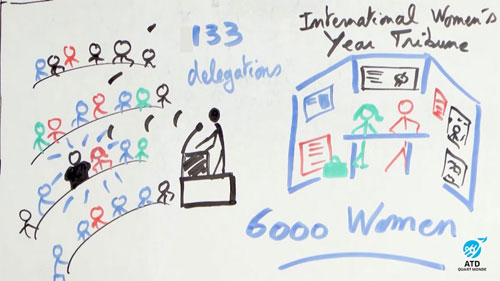

When the United Nations organised the first-ever World Conference on Women, in 1975, Mary was there. Before travelling to the conference in Mexico City, she interviewed many women living in extreme poverty. One of them told her: “If you’ve got nothing, you go without, and you’re not even thought of. […] When I heard about Women’s Liberation, at first I thought it was a good idea. But then after hearing two or three of them talking on the television, I came to the conclusion that there was only a certain class of women speaking out for women as a whole. They are not from all classes. And we all have different needs and different wants. […] I don’t agree with what they say on my behalf.” Mary was determined that the voices of women in poverty be heard at the conference. When it became clear that it would be impossible for to give a speech, she recruited the housekeeping staff of the hotels where diplomats were staying in order to slide ATD Fourth World’s message onto dining tables and pillows.

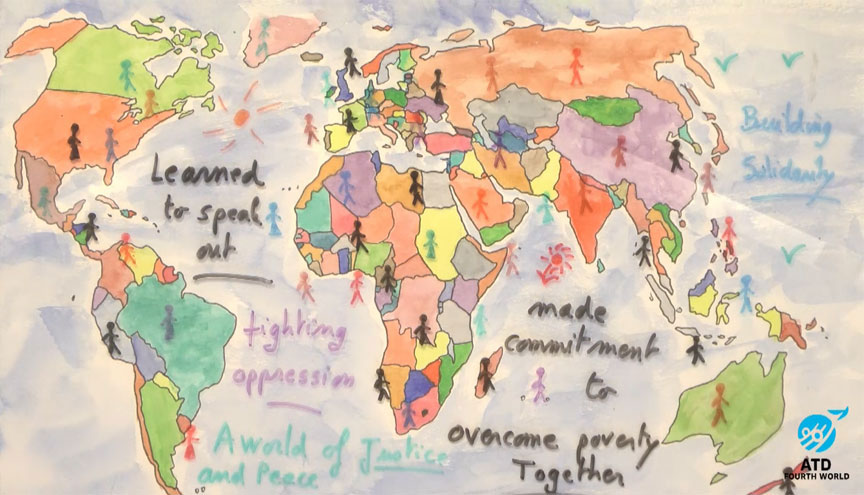

At subsequent World Conferences on Women—in 1980 in Copenhagen, and in 1985 in Nairobi—Mary was able to take the floor, chair a workshop, and influence the governments’ decisions. However, despite these conferences, Mary remained concerned that “gains made have not benefited all women equally, and that women in the lowest socio-economic groups have benefited least of all”.

As important as access to family planning was, in the UK Mary saw it beginning to be used in a coercive way to curb population growth among people in poverty. She told governments:

“We are quite concerned about risks for the most disadvantaged women and their families when policies intended for the well-being of all are not carefully monitored. […] Some couples in poverty have sterilisation proposed to them when they are very young and do not want to take such an irreversible step. Some doctors, when they have just delivered a baby, then sterilise the mother without her consent. Many poor women (and men) think that doctors are inclined to decide for them, rather than helping them choose. They resent being pushed into an abortion because of bad housing or low income, or because others think they already have enough children. Coercive sterilisation or abortions are most likely to occur among the poorest families. Women in poverty also noted that even if people are needed to foster and adopt unwanted children, ‘The likes of us don’t get a chance to take care of those unwanted children.’ […] Addressing parental rights and responsibility, as well as free choice in family planning, requires the utmost sensitivity. We must consider the actual experiences of very disadvantaged families through several generations.”

This and the content of other videos in the series will be published in Joyful Revolution: Poverty, Social Justice, and the Story of Mary Rabagliati. [Publication pending]