The Creation and Endurance of Frimhurst Family House

This article is imported from our 2017 Stop Poverty Campaign web site.

As part of the commemoration of the International Day for Eradicating Poverty organised by ATD Fourth World UK in Frimhurst Family House on Saturday, 21 October, the following presentation was given by Dr. Michael Lambert, a social historian from the University of Liverpool, on the historical context and significance of Frimhurst’s creation and endurance.

Frimhurst and Its Early History, 1957-77

Frimhurst 60th anniversary event, Frimhurst

Michael Lambert, University of Liverpool

(1) Introduction

I completed my PhD thesis at Lancaster University in 2017 on what authorities then termed ‘problem families’ during post-war welfare state period from around 1945-74. This focused on residential centres intended to supposedly rehabilitate these ‘problem families’ back into the wider life of the community

Two things quickly became apparent.

Firstly, the label ‘problem family’ is a loose, elastic, indistinct and indefinable, and hard to grasp term which authorities used liberally to describe any number of families. It focused on behaviour. It overlooked the difficult personal circumstances in which families lived, along with their voices. Reading through thousands of case files, it soon became apparent that missing from the discussion was the word poverty, as well as the views of those labelled a ‘problem family’.

Secondly, Frimhurst stood out as different. In post-war period there were six residential centres run by voluntary organisations. The first in Marple run by Lancashire Community Council and staffed Quakers called Brentwood, opened in 1937 and closed by 1970. Second in Plymouth the Mayflower was managed by the Salvation Army and ran from 1948-62. Third the Elizabeth Fry Memorial Trust House originally called Spofforth Hall near Harrogate but later moved to West Bank in the heart of York which was organised by the Rowntree family charities, running from 1950-72. Fourth Crowley House in Birmingham operated by the Cadbury family charity from 1956-73. Fifith, St Mary’s Mothercraft Centre in Dundee which has roots in Presbyterian and other religious groups supported by the Bishop of Brechin operated from 1953 to 1974. Sixth, and opened last in 1957, was Frimhurst. It remains open to this day.

Whilst Frimhurst was modelled along the lines of other centres – focusing on the behaviour of families, teaching mothercraft, cooking, cleaning, child care and all supervised by matriarchal staff focusing on domesticity – it was different. Frimhurst, from very early in its history, saw families not as ‘problem families’ but as families in trouble, families with problems, and struggling to get by. The regime was not strict or severe, and any changes were not imposed by forcing mothers to learn new methods of caring for house and home, but in dialogue with families about what they saw and experienced as their own difficulties. In the context of the post-war period this was very radical, and one of the crucial reasons why Frimhurst has outlasted all centres. This difference will be the subject of the talk today.

(2) Post-War Britain

Image: The Times, 21 July 1957

Image: Liverpool Record Office, HOU/189/35 Grove Street, Liverpool Housing Committee, Falkner Street Area Clearance Photos, 1966.

During a speech to the Tory Party faithful in the Summer of 1957, the then Prime Minister – Harold Macmillan – stood up in front of the crowd and famously announced that Britons have ‘never had it so good’. The economic growth after the end of the Second World War, a political commitment to full employment and the welfare state had created unprecedented affluence for thousands across Britain. Just before the ‘Swinging Sixties’ took hold, rationing had ended and people were less fearful of the ravages of poverty which were recent in the mind from the period of the Great Depression in the 1930s.

However, not everyone in Britain had ‘had it so good’ and one of the accompanying images from a slum clearance project in Liverpool from 1966 – with portions still occupied and inhabited – shows difficulties of living in Britain for many during this period. I will now focus on some – but not all – of these difficulties to illustrate the other side of post-war Britain.

Housing. Pre-war slum clearances had been halted by the outbreak of war in 1939, as had house-building. On top of this, many major British cities had suffered serious damage from the Blitz. By 1945 this left thousands homeless and in temporary shelters or billets accompanying wartime evacuation. Council house waiting lists, particularly in the larger cities, expanded by the day into the tens of thousands. Rent control also meant that many landlords allowed their properties to fall into disrepair, or divided larger properties into many flats or rooms to maximise their income. Bringing up families in such conditions was difficult at the best of times.

Work. The post-war economic boom created opportunities for many, but hours were often long or pay remained low, particularly for industries which were not as skilled, which affected growing numbers of women who entered work. Working conditions were often difficult or lacked protection, resulting in illness, injuries and other issues which made getting by more of a struggle. Work was not the route out of poverty and hardship claimed by the post-war consensus.

Women. If housing and work problems aggravated difficulties and struggles in life, then these burdens primarily fell on the shoulders of women as mothers. The state saw women’s role as carers and mothers rather than as people and citizens necessarily in their own right, and although child benefit – then called family allowance – was introduced and given directly to women, it did not change this balance of power within the home. Male control over money and its use for themselves – in leisure, gambling, drink or their own pursuits or interests – meant women, those in hardship and struggling with poverty – did certainly not have it so good.

(3) ‘Problem families’

Image: Lancashire Archives: CC/CWV/2, Lancashire County Council, Our growing family (Preston: Lancashire County Council Children’s Department 1961).

The attitudes of the state, local authorities and those in government at all levels frequently saw the problems of housing, work, women, poverty and others described earlier not as larger problems with society, but with individuals, families and particularly mothers. If Britain ‘had it so good’ then a failure to prosper in these unprecedented conditions was not the responsibility of the government, but of people, of families, of mothers. They largely ignored the views and demands of those experiencing these issues and instead preferred to plan on their behalf, wanting to change their behaviour to fit in with the new post-war consensus.

Several studies undertaken by a range of experts – including the Eugenics Society, wanting to rehabilitate their image after the bad publicity they received due to the Nazis and the Second World War – sought to give scientific legitimacy to the ‘problem family’ label which was, effectively, a stigmatising and blaming term which focused on government criteria for causing difficulties to welfare services, rather than anything to do with families themselves. These studies meant that ‘problem families’ – however loosely understood – were the subject of great interest to post-war state services.

The image of a white-clad child care officer wearing gloves and making decisions on the mother’s behalf captures this from a Children’s Services pamphlet created by Lancashire County Council from 1961.

Social workers and others at the time used the label ‘problem family’ to describe and categorise families, as well as open up particular forms of action and intervention. These included intensive social work visits, perhaps daily from workers specifically employed by local authorities, or employed on their behalf in voluntary organisations such as Family Service Units. Sometimes families were relocated – or even segregated – in special housing: often slum property deferred for demolition, huts in disused military sites far from home, or hard-to-let decaying council property, all of them physically and socially isolating ‘problem families’ from friends and family, as well as the wider community. Authorities thought that they could keep a closer eye on such families as well as keeping them separate from others.

Often the final – and most expensive – resort was for local councils to sponsor families to spend a period of time at a rehabilitation centres run by voluntary organisations. As noted at the beginning, there were six of these from roughly 1945 until the middle of the 1970s. Their regimes were mainly focused on domestic skills and stays were anything from 2-6 weeks for some, 2-3 months in others, or very rarely up to 6 months. Local authorities measured their use on whether the family presented less of a ‘problem’ to their services when they returned, and social workers judged families to be a ‘success’ or ‘failure’ by whether they continued to place undue demands on their time and resources.

It is here that Frimhurst enters the story. But, as mentioned at the beginning, it was always a little different and provides clues as to the reasons that it has survived to the present day.

(4) Grace Goodman and Margaret Gainsford

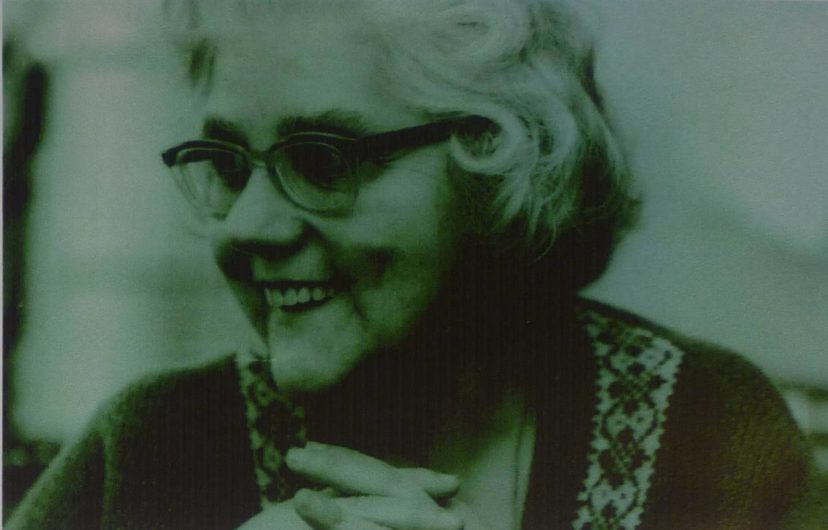

Image: Centre International Joseph Wresinski: XH113, V11, 2 GB Mrs Grace Goodman 2000.

Individuals made all the difference in cultivating an atmosphere of difference at Frimhurst. Unlike the other centres, Frimhurst was not started by a larger organisation or by the backing of big philanthropists, but by two women dedicated to making a difference. They gained the support of a host of local authorities in and around London, as well as smaller financial support from those in voluntary organisations they were well-connected with.

Both Grace Goodman and Margaret Gainsford had worked as social workers and marriage guidance counsellors employed by London County Council, working exclusively with so-called ‘problem families’. Primarily in areas of distinct poverty – London’s East End, portions of Kensington occupied by the first waves of migrants from the SS Empire Windrush, and the slums of Islington and North London – they saw personal relationship as essential to helping families, and believed that families should be active participants. Decisions should be made together, between those in poverty and those wanting to help them.

This is reflected in the opening of Frimhurst.

From the beginning, whole families were to be admitted rather than simply mothers and young children as happened at other centres. The founders of Frimhurst recognised that any change to be instigated together. This also prevented profound physical and emotional disruption caused by temporarily breaking families apart to rehabilitate them.

Families lived in separate family units rather than in large dormitories or shared rooms, and were not supervised by the overseeing warden or matron but by each other in sharing space together. Such was the demand that four pre-fabricated bungalows were erected in the grounds soon after Frimhurst opened to ensure each family had sufficient living space. The idea of the family as a unit was central to the ethos at Frimhust, and Mrs Goodman and Mrs Gainford would not compromise this to increase the numbers of those admitted.

Unlike the other centres where visits were temporary and mothers were largely cut off from participating in the local community, families were expected to find work, live and settle into life at Frimhurst and not just have short-term visit in domestic instruction. Children went to the local school, attended playgroup or used the nursery rather than lived in isolation from the local community. As social work attitudes and ideas changed, these pioneering methods of Frimhurst were copied by other centres hoping to improve their image and methods.

The duration of admission was, unlike other centres, for a minimum of six months, with many families staying significantly even longer, sometimes over a year or years. This meant that it cost much more for sponsoring local authorities who became much more selective in how they chose families compared with other centres, sending fewer families for longer stays. Often, those who were referred by social services were those considered by such authorities to be the ‘worst’ or ‘last chance’ cases.

Relationships were also the centre of attention at Frimhurst, rather than trying to educate mothers in domestic chores and into good standards of caring. Regular meetings between parents and families with either Mrs Goodman or Mrs Gainsford, or simply between families, were used as opportunities to discuss and talk about issues – both positive and negative – enabling everyone to become active participants in processes of family change. Family functioning as understood by the family was essential as a mode of operating in the house.

Material elements were also firmly present as Frimhurst only admitted families who already had, or were guaranteed a home. Their personal investment matched the financial one of sponsoring bodies as well as time spent in the home.

(5) Frimhurst

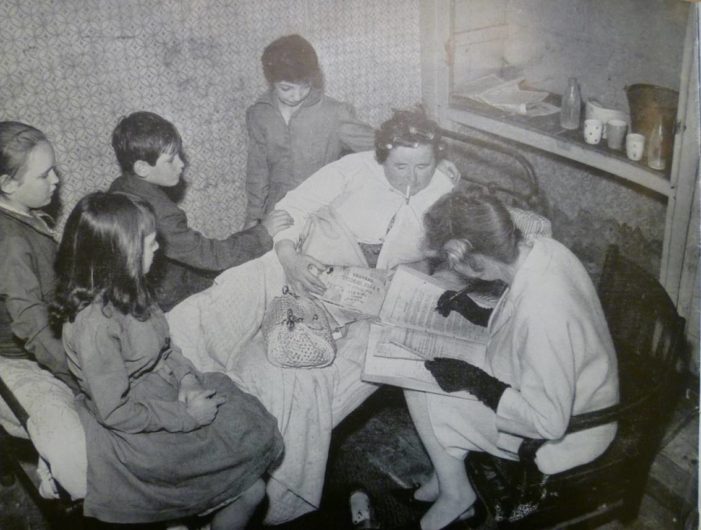

Trying to capture life at Frimhurst is difficult through dry and limited archival sources documenting meetings and reports about families, but a newspaper article in the Sunday Times written by a journalist who visited during October 1963 does some justice:

‘In a rambling, shambling, Victorian house in Surrey, families in danger of disintegrating or who, through circumstances that have become too much for them, have lost the ability to cope with life, are learning to live again… Frimhurst is the last hope, the alternative to the family breaking up and the children being taken into care by the local councils… There is no atmosphere of disapproval, no feeling that they are failures, no exhortations to be clean, be tidy, be sensible, and the minimum of rules… But for those who run and staff the home the policy of non-interference is a difficult one. People used to a fairly orderly and disciplined existence find it terribly hard not to try to impose this on other people’.

Frimhurst was seen by those referring families to be the end of the line, the ‘last chance’ for ‘problem families’ before they were split up with children being received into care and parents being scrutinised by social work assessments. However – and this is important – families went voluntarily and were actively involved in change, rather than being subjected to a regime imposed from the centre. If families agreed to attend but did so only due to pressure from social services then often Mrs Goodman or Mrs Gainsford would arrange for their departure. Given the sometimes financial precariousness of the centre, this was a bold move, but they were committed to an ethos of partnership and anything with jeopardised that would not be formally tolerated.

The article captures the view Frimhurst did not see those who arrived as ‘problem families’ but ‘families with problems’ and used the building of relationships to amend and improve these. It also captures the very difficult personal circumstances of families, and the stresses this imposed on those working and living at Frimhurst. Diana Skelton’s talk on the life of Mary Rabagliati – an important personality in the development of Frimhurst – fully appreciates how hard, frustrating and difficult a commitment to dialogue was in practice.

(6) Reputation

Image: Centre International Joseph Wresinski: XH41, V11, GB 2, ‘Frimhurst’ Lotos, 19 (1965).

Frimhurst attracted interest and many visitors from across Britain and the world because of its reputation and mission in transforming the lives of families.

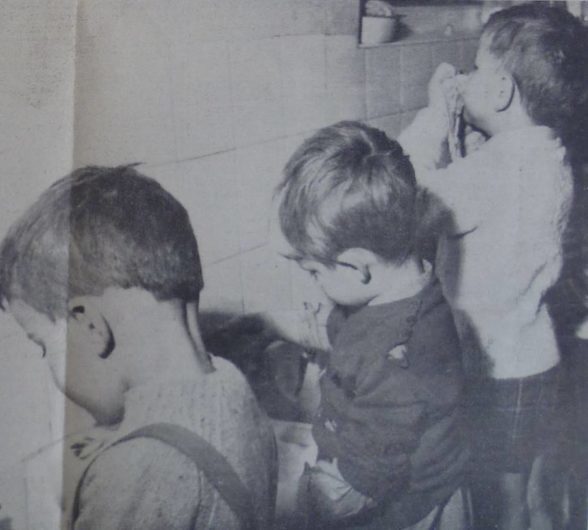

The photos from a 1965 Youth Camp which constructed portions of the outer buildings as well as playground for children captures the involvement of all in the process and the daily atmosphere of life for children, families and those who came to work – even for a short time – at Frimhurst.

Frimhurst also accepted students from social work and social science courses from across Britain on placement. Those who stayed did so for varying periods to assist the centre in many different ways. However, visitors arrived not just from universities but also from members of voluntary organisations such as the Family Welfare Association, the National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children, Family Service Units and others all wanted to help, as well as see and experience the atmosphere of the centre.

Visitors were not just national, but international. This included a chance meeting outside Frimhurst between Grace Goodman and Pere Joseph Wresinski in 1962 which led to increasing cooperation and correspondence between the two until Frimhurst formally became part of ATD Fourth World in 1967, with the first official volunteers from ATD Fourth World arriving in 1968, including Mary Rabagliati. Pere Wresinski had visited many of the other residential centres during a tour of local authority and voluntary organisation ‘problem family’ programmes in 1961 and 1962, but did not keep contact in the same way he did with Frimhurst. With the family house becoming formally integrated into ATD Fourth World, this allowed for a greater degree of financial stability and continuity in the organisation which had previously regularly sent out appeals for funds. It also provided continuity in staffing, who often came and went over quite short periods due to stress and the lack of time off or away. Life at Frimhurst was a vocation rather than a job, and this caused many staff to leave.

Mrs Goodman was also asked to speak about Frimhurst up and down the country, and used such occasions to request funds as well as publicise their work. Above all, it was the different atmosphere of Frimhurst, the active involvement of families, the length of stay and the relationship support for the whole family which made it different to other centres. This is shown quite visibly in the comments by a visit from the Wardens of Brentwood in 1969 – Mr and Mrs Hatton – who felt conditions were ‘very primitive’ compared to their own regime, with several remarks in a report to the other centres containing concerns about the ‘chaotic’ feel and the lack of control exercised by the staff.

Indeed, in 1964 there was a concerted effort by a number of local authorities who had originally supported Mrs Goodman and Mrs Gainsford in their venture at Frimhurst, along with pressure from other voluntary organisations to make Frimhurst more like the other centres as they were ‘tried and tested’, less permissive and more rigid in their structure. This caused a lot of internal problems within Frimhurst and extensive, lengthy discussions about methods among the staff and others – including from the historians point of view, the decision to keep official records on families!

However, with the backing of the Medical Officer of Health for London and the departure of some staff who didn’t quite see eye-to-eye on the ideals promoted in the family house, Frimhurst was able to secure enough backing to continue on its more liberal model for years to come. This was cemented in 1967 with the formal alignment to the ATD Fourth World movement.

(7) Difference

Image: Centre International Joseph Wresinksi: XH41, V11, 2, GB, Shirley Toulson, ‘Children with problem parents’, The Teacher, 26 February 1965.

Image: Centre International Joseph Wresinski: XH50, V11, 2, GB Families in need, 1975

This difference helped Frimhurst to survive. As noted earlier, the other centres increasingly copied the model of Frimhurst, if not wholeheartedly. When all the other centres were closing at the beginning of the 1970s due to changes in the law, the opening of centres by local authorities directly, and reduction in permissive powers to send families, Frimhurst endured. The period of the middle of the 1970s – where this early history finishes as does the ‘golden age’ of the ‘welfare state’ – saw the post-war Britain described by Harold Macmillan come to an end. Unemployment, a series of strikes and labour disputes, the 1973 oil shocks caused by war in the Middle East and the weakening of the pound and the consensual Keynesian economic model meant many of the foundations crumbled. Expensive rehabilitation centres run by voluntary organisations were one of the first items to be cut by councils, authorities and sponsors who were struggling for money.

Looking back at histories of other centres I usually close by stating how many families went through, where they came from and what this says about how the centres were run and attracted local support. Certainly for some of the period, this was true of Frimhurst, with most families coming from London or the Home Counties – until other centres closed and drew in referrals from across Britain – but once again Frimhurst is different. I cannot give a categorical figure because it is still accepting families. Over 189 had gone through by the time of their ten-year celebration in 1967, but this includes families who stayed for very long and very short periods of time. However, Frimhurst continues to admit families – in a very different manner from even the 1960s and 1970s but with a commitment to the same ethos – and still changing the lives of those who come through its doors.

Closing this talk on the images of children is important as it is those who are affected most directly and most significantly. Speaking with those who lived at Frimhurst later, as well as the exhibition as part of the 60th anniversary events, I am struck by how Frimhurst lives on through the memories of those who went as children, and how the ethos continues through their outlook. The letters from mothers to Grace Goodman or Mary Rabagliati contained in the archives at the Centre International Joseph Wresinski provide a real testament to the impact they had, and how their relationships impacted on their lives beyond the walls of Frimhurst. Many enclosed photographs of children at play, or in a new home, or holidays, or sent Christmas cards years later to recollect memories and the experiences they had. Frimhurst endured as part of their lives, as much as their experiences.

I will finish by reading one of these letters in full from the late 1960s as it captures everything discussed so far in relation to Frimhurst. I have removed any identifying details to protect the privacy of those involved, but have kept everything else in order to retain its truth in speaking volumes about the issues touched upon in this talk.

I have only given a very brief sketch of the centre and have missed out many names, personal events and tragedies, memories and experiences. However, by offering a flavour of what Frimhurst was, is, and above all why it is different from its comparators in seeing people as participants rather than subjects or victims, I hope I have captured some of the reasons why the centre remains open to this day.

It is also appropriate to finish on the words of those who went, in the same spirit of working in partnership and listening to those in poverty, as well as being indicative of those families who passed through the doors of Frimhurst in all those 60 years.

(8) Letter

“Dear Mary [Rabagliati],

Received your welcome parcels on Tuesday. Since I left Frimhurst a lot has happened. I got bashed up and black eyes so I went and lived in a hostel for a week. I came back Monday for the sake of the children. He never paid the rent in arrears for £20, never paid the coal bill £10 and there is a lot more that comes to nearly £60 all round. I nearly came to a dead end tonight thinking is it worth all the worry and shame and the bad name you get with it.

But I keep thinking of Frimhurst and the happy times I had there so it helps a little bit and sometimes I really give up hope and think I would be better off dead and out of all this worry and you know what I mean. Anyway I want to thank you and all the staff for giving me and the children a happy time. I really love Frimhurst and the boss very much even if she does shout at me now and again.

That was the first birthday party I have ever had since the day I got married. I cannot show my feelings very well but I think a lot of you and Marie Frances. And Mrs Goodman just been like my own mother when she was alive. I am very honoured to think that someone really worries about me. Thank you Mary very much I will always remember that and it gives me a bit more to think on before I do anything daft.

He’s gone for a few days now. Left all the worry behind. I sold my small wireless for £4 and my one and only coffee table and got £3 for that. Sold [eldest daugher’s] doll pram for £2-10 and sold our [other daughter’s] watch only got £2-5 so I nearly got £12 so I paid my electric bill and got the lights on. The kids understand but they feel it. But you have got to do something. God knows about the rent I went for a loan. But I could not get one with him walking out. So someone wanted my electric fire for £5 this week so that will pay someone off.

I am going round the bend again. I cannot take the boys out this week as they will have to live on fresh air I will leave them for another 2 weeks until I can try and get out of this mess one way or another.

Sorry to give you all my troubles Mary but I can talk to you rather than anyone else anyway. Keep up the good work. I can tell you this, I would not go back to that hostel again. I have never been in one and I would sleep in a tent before it came to that again. Anyway God Bless keep you safe. I got a lot of postcards from all over the world from the working party at Frimhurst. Got them on the world it was a lovely thought and I had a little cry. Write to me Mary please it is something to hold on to. Is Mrs Goodman back yet?

God keep you safe as always.

Love from me and my family.

Have you got a new car yet?”