Friendship, Education, and “Grease” Connect Children in India to Tapori

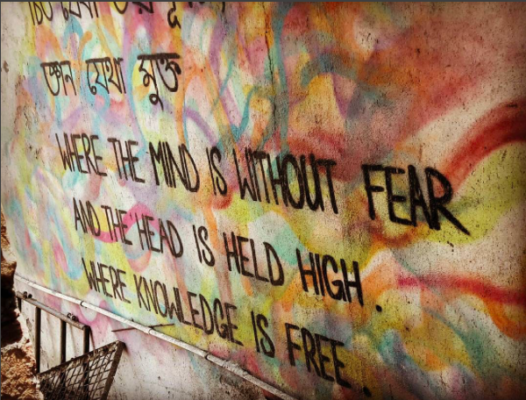

Above photo courtesy of Tiljala SHED.

Cycles of history come to mind when visiting India. In 1967 it was on a visit here that ATD Fourth World’s founder, Joseph Wresinski, drew inspiration to create the Tapori network of friendship among all children. He heard the word “tapori” being used to insult children who lived on the streets or in train stations. At the same time, he noticed that these “tapori” children shared with each other any food they could find. To honour that spirit of sticking together despite a difficult life, he chose the name Tapori for a worldwide movement of children from all backgrounds who can show adults what it means to build a world of friendship.

A half-century later, after having flourished in many other parts of the word, Tapori has returned to India, thanks to Mamoon Akhtar. Mamoon who grew up in Tikiapara, a run-down district of informal housing on the outskirts of Kolkata. Because he had to drop out of school when his father could no longer afford school fees, he has always thought that it is important for all children to have a chance to learn. In 1999, this led him to begin tutoring a few children of his neighbours in his own home. Soon, there were 25 children studying with him. Over the years, his determination never to turn a child away has led him to broaden this effort into several schools that now reach more than 4,500 underprivileged children. Mamoon says of Tikiapara, “Low quality of life and inadequate opportunities [led] many to turn to drug-peddling, rag-picking, and prostitution to eke out a living.” His Samaritan Help Mission (SMH) is as multi-religious as the diverse community it serves, aiming to create opportunities for all, and particularly to achieve communal harmony and 100% literacy. To this end, they are currently renovating their main school building to optimise physical access for children with disabilities.

Of himself, Mamoon says, “I am not a social worker. My work is more like that of a mechanic for young people. I spend time with young people in the street, and when I see a problem, all I do is add a bit of grease to help them out.”

Just down the road from SMH’s main school, Tapori has also been present at the Don Bosco Ashalayam, which runs a night shelter for children living in the streets. Established in 1985, the Ashalayam is a project for destitute children irrespective of caste, creed or gender. Run by the Salesians of Don Bosco, the Ashalayam today runs six homes, a research and rehabilitation project, as well as educational and vocational programmes. The prime aim of the Ashalayam is to offer a friendly and helpful environment for children to empower them to claim their rights to survival, protection, development and participation.

On a recent visit to India, ATD members based in the UK were also able to introduce Tapori to the Tiljala Society for Human and Educational Development (SHED), a voluntary organisation of social activists in Kolkata. Founded by Mohammed Alamgir, who grew up in a marginalised community of illegal housing, Tiljala SHED aims to end all forms of exploitation, promoting dignity, equality, justice and peace. The founder’s son, Shafkat Alam, runs many programmes for children who are victims of trafficking, at risk of early marriage, working as rag pickers or otherwise vulnerable.

He notes the importance of helping both boys and girls, saying: “Because of the recent, understandable bias toward the girl child in funding, it is common to see girls getting a degree, but extremely rare for boys. Illiterate or poorly educated boys are vulnerable to drugs, crime, and other social evils. Moreover, the educated slum girls are still most likely to marry poor boys from the slums. The education difference between them can be a cause for family strife.” In addition to prioritising the needs of the most marginalised children and families, Shafkat also reaches out to children from privileged backgrounds, giving them a chance to discover a community in their own city and to contribute to it, for instance by helping to paint their school building.

A fourth non-profit organisation in India is also now connected to Tapori. Vasundhra Om Prem, the director of the Centre of Excellence in Alternative Care of Children, has been motivated hearing the song “At Tapori,” inspired by messages from children around the world. Vasundhra calls the song ”mind-blowing” and adds “Tapori is all about child participation. I am very much interested to learn how in India we can promote child participation and how both our organisations can collaborate.”

All these links among girls and boys of different social backgrounds and religions reflect Wresinski’s vision for children everywhere and bode well for increased Tapori connections.