Myth: People in Poverty Lack Political Intelligence

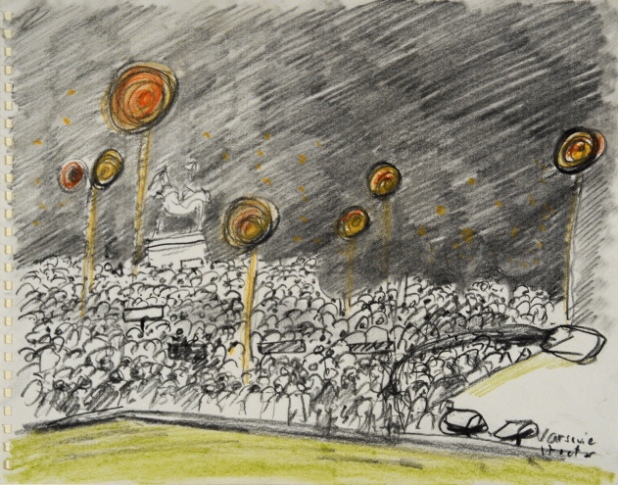

Drawing above: World Day for Overcoming Poverty in Warsaw, Poland – AR0200114002 © Jean-Pierre Beyeler

These days there’s a lot of talk about protecting yourself from illness, and of course that’s necessary. But another concern is that the measures taken to deal with COVID-19 are driving many of our fellow citizens to hunger. All over the world people in poverty are severely impacted. In the text below from The Poor Are the Church, Joseph Wresinski evokes the period of time around May 1968 in France, when hunger was also present in cities and shantytowns. Wresinski interviewed by Gilles Anouil.

- Joseph Wresinski: We have moved on, I think, especially since 1968, a year that we did not experience in the same way as others. Then, the majority of the working class thought, as it did in 1936, that it was the age of a new liberation and a step leading to a more just society. In the low-income housing projects, we discovered that the underprivileged were not only deprived of rights, but were also excluded from the struggles for human rights. They were neither present nor represented anywhere. In 1968, we began to speak publicly of the underprivileged as a people and their right to representation.1

Gilles Anouil: Didn’t the underprivileged then join the protesters in the streets?

- Wresinski: A few younger ones did, happy to seize the opportunity of merging with the others. But most people didn’t budge; they were near starvation. We came to understand then that people who had “nothing to lose” could not participate in the struggle, as could those who had some reserves. The poorest lost the jobs they had obtained after much effort, and their allowances were not paid for some time. I saw entire areas where all the families had to live for a month from petty larceny, charity and alms. Municipal social services, which should have given priority to supporting those families, did not grant them any sum of money on the pretext that they were not regularly employed workers.

- Occasionally, students would go to a shantytown when they had some food left over after supplying workers on strike, and they unloaded food that often was spoiling. Once I saw the arrival of a supply of fish already going bad. It was thrown on the ground, and people were fighting for a share of it. Seldom have I had so strong a feeling of being in the depths, with people bound hand and foot to a common destitution, a common humiliation.

- May and June of 1968 were months of starvation in the low-income housing projects and, on July fourteenth, we organized our first Human Rights Festival. It took place at La Cerisaie in Stains; in May we had started a students’ movement called “Knowledge in the Street.”2 For the fourteenth of July, the students wrote and staged a play telling the story of the poorest in the French Revolution. Our volunteer corps was becoming indeed a defender of human rights.

Anouil: Weren’t you abandoning your line of conduct of not embarking in struggles that remained outside the families’ scope? They could not possibly have acquired sufficient political sense for that kind of a struggle.

- Wresinski: Poor people’s lack of political sense is a myth invented by the rich. It is probably true that our abstract ways of treating political questions in the name of our doctrines cannot have any interest for men and women constantly obliged to face up to concrete difficulties in order to safeguard their existence and dignity. But you only have to share and analyze these real-life situations with them to become aware of the political realism of the Fourth World. It also reveals to us the degree of abstraction and lack of realism found in other social groups.

- […] This intolerable situation forced us to change course, which we did with the families’ constant agreement and even encouragement. Their situation of near-starvation had forced us to collect money and food. The families were invited to form local committees to organize the distribution of money and food according to each person’s needs. It was the first time in France that a truly collective responsibility was being taken on in the poorest housing projects. The debate about giving priority to the poorest, to the hungriest, and to the most neglected children became a central one and was brought to public attention. The families carried out their task most honorably during those weeks, in all the places we were able to visit. In the process, they became more aware of their existence as a people. Those who had known us for a long time found it quite natural that we extend our action to other places previously unknown to us. They exchanged grievances with one another.

We had known for years our mission. It is to bring a people out of the shadows so as to help them make their mark on history and assume their role vis-à-vis their fellow citizens.3

- May and June 1968 constituted a climax that allowed us to translate those aims into action for human rights. This strengthened the volunteer corps as it discovered a new atmosphere, new tools and a new strategy.

Purchase The Poor Are the Church from ATD Fourth World France.

Purchase The Poor Are the Church on Amazon.

- Original translation: In 1968, we began to speak publicly of “a people” and its right to representation.

- Launched in June 1968 with students in the wake of the May events. Knowledge in the Street invited privileged young people to come and share their knowledge with children from disadvantaged neighborhoods. From this Street Libraries were created and spread throughout the world in places where ATD is present, bringing books but also other cultural activities, singing, poetry, music, drawing, painting, computers…

- Original translation: We had known for years that our mission was to bring to light a people, to make it leave its mark on history and assume its role vis-à-vis its fellow citizens.