People in Poverty Know How To Improve Support Systems

In April, 2021 ATD Director General Isabelle Pypaert Perrin addressed the UN Commission on Population and Development. She spoke at a webinar on “Family Support Services and Impact of the Coronavirus Disease on Food Security, Nutrition and Well-Being“. Below is a shortened version of her statement.

Video of Ms Pypaert Perrin’s statement in English, found below.

Play with YouTube

By clicking on the video you accept that YouTube drop its cookies on your browser.

Lisa and Kevin: a family shattered

Yesterday, Lisa and Kevin, a young couple from France, lost custody of their three-month-old twins. At the same time, they were evicted from the family shelter that took them in when their babies were born. At the time, they were homeless.

Lisa and Kevin have a long history of hardship but also of strength and perseverance. When they moved into the shelter, they thought they could finally live as a family! But from the start, professionals in the shelter saw their poverty and doubted their ability to raise young children.

Nobody offered to help the young father find training or work. So Lisa and Kevin were together 24 hours a day in their room at the shelter. They began to argue. They also left the shelter often, something French health measures forbid.

The social workers started to fault them for this situation. Things got heated. The system decided to place Kevin and Lisa’s children in care. This meant the parents would have to leave the shelter. They were thrown out on the street while the country is under lockdown.

Parents learn not to ask for help

Why is it that what is supposed to support parents often turns into control over families with the hardest lives?

Because of this, many of the families ATD knows are reluctant to ask for help. Based on experience, they fear family support services will interfere in their lives.

They know the system could easily put their family under a microscope and then shatter it.

Often other people blame these families for their situation. Because the system sees them as responsible for their problems, it does not trust them. Nobody sees or shares their hopes. It is as if the tremendous efforts they make to improve their lives are simply invisible.

- So solutions designed for them, but not with them, are imposed on them. This is why, too often, policies and programs backfire on families living in poverty.

ATD research: a more complete picture of poverty

Lisa and Kevin’s situation shows how families in poverty face deprivation in many areas at the same time. In addition, they often experience social and institutional maltreatment. ATD’s recent participatory research, conducted in partnership with Oxford University, demonstrated this clearly.

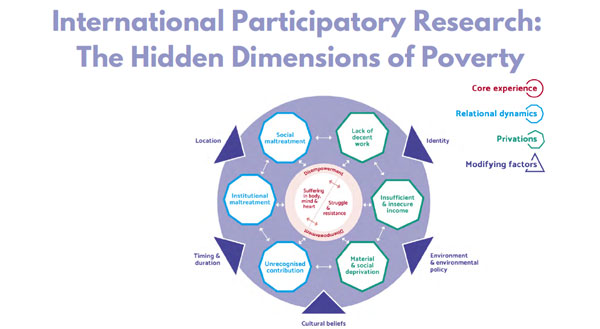

In this research, participants worked together to identify dimensions of poverty. Because the reality of poverty is complex, it cannot be captured in a few simple characteristics. Using the Merging Knowledge methodology, the research project explored what people in poverty know from experience. Researchers considered this knowledge as equal to that of academics and professionals such as teachers or social workers. Together, they identified nine key dimensions or characteristics of poverty.

Three of these concern relationships and involve social and institutional maltreatment. Other people often ignore the strength and experience of people in poverty. In addition, what they do to help those poorer than themselves remains invisible.

- When you know what it’s like to be rejected, you open your door to others. And yet people tell you, “It’s irresponsible to bring homeless people into your home when it’s already overcrowded”.

And at the heart of the experience of poverty is suffering, the research found. Frequently, this suffering—in mind, body, and heart—is caused by disempowerment, a result of deprivation and maltreatment. Central also to the experience of poverty is the way people respond to it through struggle and resistance.

Considering these characteristics of poverty, we can see how the pandemic and measures to deal with it have made life even worse for families in poverty.

People in poverty step in when government programs don’t reach the most vulnerable

Alicia is an ATD Fourth World activist and young mother in Latin America who has been through difficult times. She lives in a shantytown with her mother and other family members. One night, Alicia and her mother could not sleep. Both women were worried. They were thinking about Veronica, who can no longer sell doughnuts after school because of the lockdown. They also worried about Felipe, who can’t go out to collect the plastic bottles he resells for a living.

In normal times, people in extreme poverty do not have access to decent jobs. The work they find is unstable, dangerous, and poorly paid. During lockdown, they can’t even hope to find this kind of work, which is their only source of income.

- That night, Alicia and her mother saw clearly that if nothing were done, neighbours would be dead in two weeks’ time. Not from the coronavirus, but from hunger.

So Alicia, who now has a stable job, got together with her neighbours. They reached out to others who have a bit more security too. Together they got a solidarity project off the ground to share what they have. “We will stand together”, Alicia told the ATD team helping with the project. “When the crisis is over, we’ll be able to say that we didn’t abandon anyone.”

Alicia knew that state aid would arrive at some point but that it would not reach some of her friends. Because they don’t have the right papers, these neighbours won’t be able to register on the lists for state aid.

Lack of identity papers prevents access to support

Not having identity papers also means not getting into school, receiving social assistance, or becoming citizens. Of course this makes it challenging for the authorities and organizations to reach families with the most difficult lives. Having few connections or networks, they very often remain invisible.

So, as Alicia knows from experience, sharing is a big part of community survival. In times of crisis–whether it is a pandemic, flood, or the repeated emergencies of daily hardship–families in greatest poverty count first and foremost on help from those around them.

Fragile and constantly threatened, this mutual support is not enough to end extreme poverty. But it is vital. Anti-poverty programs should recognize and strengthen such community solidarity. Too often, policies ignore these forms of support, or even undermine them.

Education or food? An impossible choice

The pandemic and the lockdowns have also made education more challenging. Schools closed and many are still not open.

Distance learning has put families living in poverty in an impossible situation.

- How do you choose between feeding the children or paying for an Internet connection to follow lessons?

How do you get materials? It’s impossible to make space for children to concentrate in cramped and overcrowded housing. And you can’t help them with school work when you haven’t learned to read and write yourself.

Many children doing on-line learning already had trouble with education. It was not their world, they felt. In a system often based on competition rather than cooperation, children in deepest poverty find it hard to succeed.

Punished for not having Internet access

In many countries, the complete shutdown of public services that people depend on has essentially become institutional abuse.

In some countries, the benefits system moved on-line. Already struggling with access and technology, people are sanctioned for not complying with on-line systems’ requirements. The result is that they have nothing to feed their families.

Covid measures damage family relationships

What’s less known is how on-line services have damaged relationships between parents and children in foster care. Visits and meetings became impossible. ATD had to fight for children and parents just to be able talk to each other once every two weeks. And that was often only by telephone. But how do you maintain a relationship with a very young child over the phone?

In some countries, families facing threats of placement or adoption of their children had to deal with family court hearings online. Without a good wifi connection or laptop, most of them had only a mobile phone to participate in these hearings.

Families had so much at stake and yet struggled to understand what was happening on the small screen. “They couldn’t see me or what kind of person I am”, one mother said.

With schools closed, some parents took part in these hearings with their children at home. Can we imagine what it means for parents to sit alone in their bedroom, hearing deeply distressing life-changing news online? How could you go and make dinner, pretending to your children that everything is okay?

Recognize families in poverty as equal partners

What families facing poverty ask is that we recognize them as actors in their own lives and as partners.

While deprivation and social exclusion might stifle their suffering, perseverance, and power to act, these things never disappear. Alicia and her family have little financial security. But they showed tremendous energy and inventiveness in organising a project to share what little they do have with neighbours.

- People in deep poverty are very smart. They only ask to be considered as equal partners in finding and implementing solutions.

But for this to happen, we need more places where they can share their experience and perspective with others. Together, we need to build a new understanding that can serve as the basis for new strategies to tackle the most extreme situations of poverty.

The former UN Special Rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights said something critical:

- “Lack of participation in decision making and in civil, social, and cultural life is recognized by the international community as a defining feature and cause of poverty, rather than just its consequence”1.

But just consulting with people in poverty is not enough. They must be fully involved in developing policies, from start to finish. This requires the time and energy to create safe spaces where people living in poverty can speak for themselves. For true dialogue to take place, there needs to be an environment of mutual trust and respect.

A guide to better policy

Covid-19 is exposing and increasing inequality and vulnerability that existed long before the virus spread. But the pandemic can also push us to ask questions. It gives us the chance to choose, like Alicia and her family, to make sure that we do not abandon anyone.

- We can choose to recognize Alicia and everyone like her as a guide to new ways of working together. And we can choose to offer parents like Lisa and Kevin something other than the destruction of their family.

Will we make this choice? Will we choose to conceive policies that actually support families in poverty by acknowledging their reality, even if we don’t understand it completely yet ourselves?

Watch the complete video of the webinar:

Play with YouTube

By clicking on the video you accept that YouTube drop its cookies on your browser.